Special to WorldTribune.com

By Natan Sharansky

These days, like many Israelis and American Jews, I find myself in a precarious and painful situation. Those of us who believe that the nuclear agreement just signed between world powers and Iran is dangerously misguided are now compelled to criticize Israel’s best friend and ally, the government of the United States.

In standing up for what we think is right, for both our people and the world, we find ourselves at odds with the power best able to protect us and promote stability. And instead of joining the hopeful chorus of those who believe peace is on the horizon, we must risk giving the impression that we somehow prefer war.

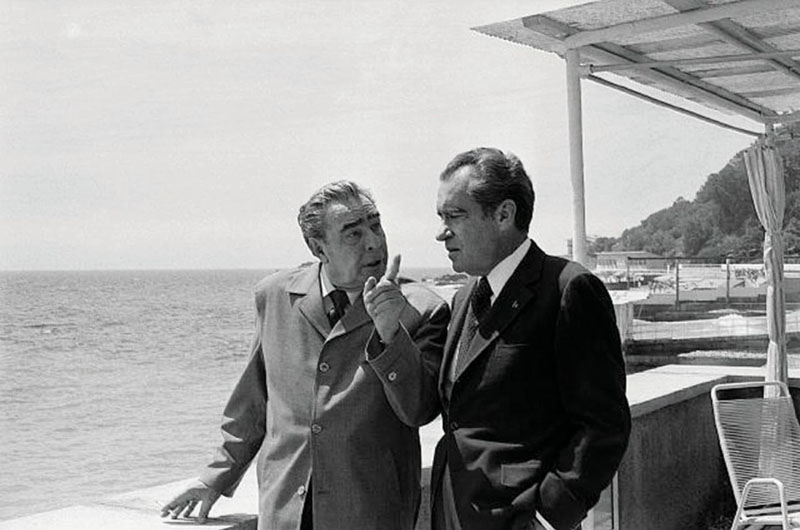

As difficult as this situation is, however, it is not unprecedented. Jews have been here before, 40 years ago, at a historic juncture no less frightening or fateful than today’s. In the early 1970s, Republican President Richard Nixon inaugurated his policy of detente with the Soviet Union with an extremely ambitious aim: to end the Cold War by normalizing relations between the two superpowers.

Among the obstacles Nixon faced was the USSR’s refusal to allow on-site inspections of its weapons facilities. Moscow did not want to give up its main advantage, a closed political system that prevented information and people from escaping and prevented prying eyes from looking in. Yet the Soviet Union, with its very rigid and atrophied economy, badly needed cooperation with the free world, which Nixon was prepared to offer. The problem was that he was not prepared to demand nearly enough from Moscow in return. And so as Nixon moved to grant the Soviet Union most-favored-nation status, and with it the same trade benefits as U.S. allies, Democratic Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington proposed what became a historic amendment, conditioning the removal of sanctions on the Soviet Union’s allowing free emigration for its citizens. …

By that time, tens of thousands of Soviet Jews had asked permission to leave for Israel. Jackson’s amendment sought not only to help these people but also and more fundamentally to change the character of detente, linking improved economic relations to behavioral change by the USSR. Without the free movement of people, the senator insisted, there should be no free movement of goods.

A critical question is, who, if anyone, will have the vision and courage to be the next Sens. Jackson and Javits.

SEE COMPLETE TEXT

You must be logged in to post a comment Login